A legacy of reform in Xiaogang

After finding success in the economic boom of China's major cities in the 1990s and 2000s, the son of a reform pioneer brings the spirit of reform and opening up back to the village of Xiaogang, where it all began.

By Zhang Jiaqi

From secret contract to making history

One of Yan's earliest memories was of a grass green jeep parked in front of his house in Xiaogang that drove away his father. At five years old, Yan could not understand the significance of the event, but he would later learn that his father Yan Hongchang, along with 17 other villagers, helped to spark a wave of nationwide rural reforms that marked the beginning of China's reform and opening up.

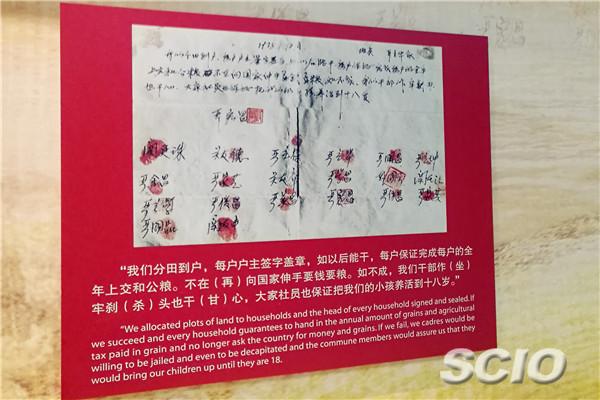

In 1978, a severe drought befell Xiaogang and the surrounding region. Fearing a famine, the villagers signed a secret contract to divide up their communally-owned farmland into individual plots.

At the height of China's old-school communism ideals, this was a big no-no. The land belonged to the collective, and so did whatever crops it produced. Assigning land ownership to individuals was sure to trigger punishment from the government. Knowing this, the 18 villagers also agreed in the secret contract—penned by the elder Yan—that in case any of them were jailed or executed for their deeds, others would take care of their children.

Fortunately, the authorities saw the merits to their ways. After all, Xiaogang in 1979 produced as much grain as in the previous five years combined, and as much oil crops as the sum of the previous 20 years. The jeep did not haul Yan's father away as a martyr, but instead held him up as a model. Within a few years, farms across China adopted the principles of Xiaogang's secret contract. The document now sits proudly in a museum, and the story of the 18 villagers is taught in China's history books.

Yan always knew he had a lot to live up to. With everything he had learned and accomplished in Dongguan, he decided it was finally time for him to go back to Xiaogang and follow in his father's footsteps.