Xinjiang's hearts, minds open up to Silk Road

Nowhere exemplifies the Belt and Road Initiative better than Xinjiang, which accounts for a quarter of China's land boundary.

At a cafe in Kashgar's renovated old town, a German family of four sat in the morning sunshine debating which type of grape was the tastiest or most succulent.

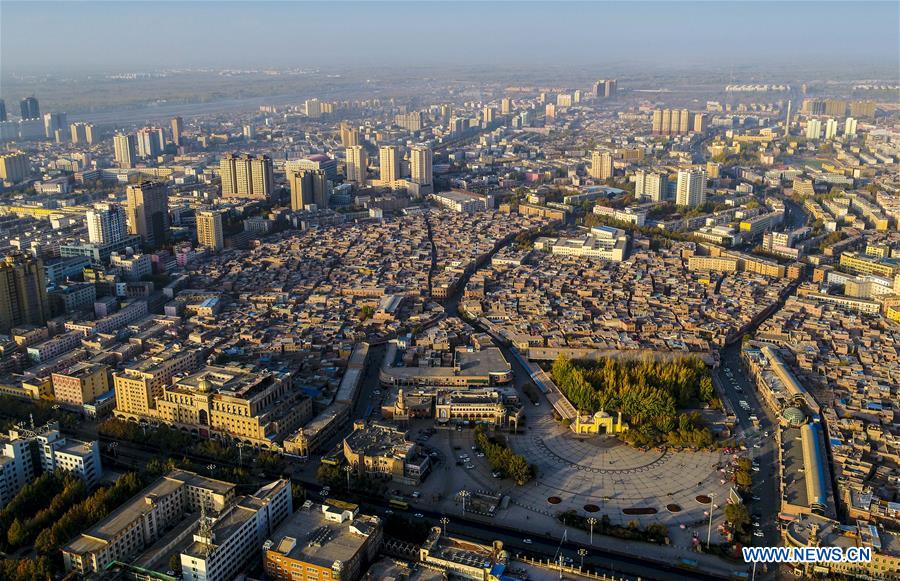

Aerial photo taken on Nov. 7, 2017 shows ancient and new town of Kashgar, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. [Photo/Xinhua]

"We bought a hundred types of Turpan grapes to eat in the car. They were all different, and each of us had our favorite," said Achim Loeffler, director of a Shanghai-based chemical firm.

"But other than that, everyone was amazed by the deserts, the mountains, the culture and the food. There was absolutely no disagreement on how delicious the lamb, noodles or naan bread were," his wife, Ute, added, while their son and daughter chuckled in the background.

After living in China for two and a half years, the Loefflers chose northwest China's Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, the heartland of both the ancient and modern Silk Roads, as the destination for the family's last trip before moving back to Germany.

"I'm curious about the old Silk Road, and I like the idea of the modern one linking the East with the West," Loeffler said, "On the trip, we saw a lot of work going on, especially in new infrastructure."

"Kashgar, for example, is old, but also very new," he added.

The ancient oasis city of Kashgar, in the westernmost part of China near the border with Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, was an important staging post on the original Silk Road and has been revitalized as a bustling hub of business and different cultures.

From Kashgar to Pakistan's Gwadar Port, there will be new roads, railways, and pipelines along the 3,000-km China-Pakistan Economic Corridor that connects the northern and southern routes of the modern Silk Road.

A one-billion-dollar renovation project has transformed most of the substandard housing in Kashgar's old town into sound, earthquake-proof buildings, while retaining the area's traditional Uyghur charm.

The old town is now a mainstay of the local economy, a favorite among young and old, locals and newcomers. Neither the mercantile culture nor the entrepreneurial spirit has waned over time.

A kilometer away, inside the Id Kah Mosque, tourists stop to stare at a wall-sized wool carpet as a tour guide explains that the 56 pomegranate flowers symbolize the unity of China's 56 ethnic groups, a sentiment echoed by President Xi Jinping when he said that all ethnic groups should hold together like pomegranate seeds to achieve national rejuvenation.

The Belt and Road Initiative was proposed by Xi in 2013 to boost world trade and connectivity through a land-based Silk Road Economic Belt and an oceangoing 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.

Nowhere exemplifies the initiative better than Xinjiang, which accounts for a quarter of China's land boundary.

Home to dozens of ethnic groups, it occupies a sixth of China's territory, although habitable oases only cover 9 percent of its area. Despite the barren landscape, Xinjiang is a frontier of cultural exchanges, transportation, and trade.

Key pass

In his 1893 adventure novel "Claudius Bombarnac," Jules Verne envisioned a "Grand Transasiatic Railway" running from the Caspian Sea to Beijing. Back then, the idea of a rail link across Eurasia was almost as absurd as launching men to the moon with a cannon.

Men have, of course, since reached the moon, though not by cannon, and the dream of the railway has become a reality. But even the sci-fi writer could not have imagined the scale of today's China-Europe freight rail lines, the arteries of the modern Silk Road.

Between March 2011, when the first line opened, and the end of June this year, over 9,000 trips delivered nearly 800,000 containers of goods, connecting 48 Chinese cities with 42 cities in 14 European countries. The cost of rail freight is only 20 percent of the cost of moving cargo by air, and three times quicker than shipping by sea.

Centuries ago, the Alataw Pass -- about 460 km west of Urumqi, Xinjiang's regional capital, and 680 km northeast of Almaty, the biggest city in Kazakhstan -- was a windswept route through the mountains for traders on horseback. Now, 70 percent of westbound freight trains pass through it, with the roar of locomotives drowning out the howling wind.

China exported more than it imported on those trains until the Belt and Road Initiative addressed the imbalance. Zhao Jie, a Chinese waybill translator in Dostyk, the first Kazakh port after the pass, has noticed an increase in the variety of imports.

"When I started the job in 2013, the list of imported goods for translation was much duller, mostly steel and ore," he said. "Now we import electronics, mechanical parts, drone accessories, red wine, baby formula and even polyester."

The Alataw Pass has become one of the busiest trading posts on the border, linking Central Asia, Europe, and the Asia-Pacific region by rail, road, air, and pipeline.

China's first cross-border crude oil pipeline, operational in 2006, from the Caspian Sea to the Alataw Pass, now brings in 12 million tonnes of crude oil every year.

"With China and Kazakhstan each holding 50 percent, the pipeline is a great example of our close partnership and the success of the Belt and Road Initiative," said Yao Yage, head of the pipeline's operation center in the Alataw Pass.

Trading hubs

Apart from being connected to raw materials and markets, the first bonded zone in Xinjiang gives the Alataw Pass an extra edge. More than 400 companies have established bases there since 2014, and total trade volume has risen to about 8.7 billion U.S. dollars.

A local private food-processing plant now has a 4,000-sq-meter warehouse and is building a 20,000-sq-meter new one, plus a 1,000-tonne flour mill. Its manager, Hu Xuming, said, "Our annual imports of Kazakh wheat will reach a million tonnes in five or 10 years, and we will store and process all the raw materials here to be cost-competitive."

About 300 km southwest of the Alataw Pass, exporters in Horgos are grateful for improved customs clearance and simplified procedures. Yu Chengzhong, CEO of Jinyi International Trade Corp, the biggest local fruit and vegetable exporter, said the benefits have been immediate.

"It used to take 10 to 15 days to transport goods from Horgos to Russia, but now it only takes five," he said. "Customs clearance in Kazakhstan used to take a whole day, but now it's only two hours."

When Yu, from central China's Henan Province, arrived in Horgos more than 30 years ago, he struggled to make ends meet by selling fruit on the street. Now his company exports 70,000 tonnes of produce each year to neighboring countries and has increased the incomes of 1,000 farming households across China.

"The Belt and Road Initiative is a golden opportunity, a blessing for all," Yu said. "I have never seen Xinjiang safer or more flourishing than it is now."

Despite being one of the most remote and inhospitable spots on earth and the youngest city along the Silk Road, Horgos does not lack creativity. Among the city's initiatives are an economic development zone and an international cooperation center.

Established in 2010, the economic development zone ensures that companies registered there enjoy a five-year tax holiday and are exempt from local corporate tax for the subsequent five years.

The international cooperation center, straddling the China-Kazakhstan border, is the world's only cross-border free-trade zone. The movement of personnel, vehicles and goods in the zone is unrestricted, and stores and visitors pay less or no tax.

Last year, the 5.28-sq-km center welcomed over 5.5 million visitors from China and abroad, 33 times the number in 2012 when it opened, and spending hit 1.7 billion dollars, almost three times as much as in 2016.

Horgos literally means a place where caravans pass, as it used to be a trading post along the northern route of the ancient Silk Road.

In Kazakh, Horgos is known as Khorgos, a place where wealth can be accumulated. That resonates with what it is becoming today -- a regional hub of trade and commerce, a portal for China's opening-up to the west and a linchpin of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Bigger dreams

The initiative isn't just powering development in Xinjiang.

Last year, China's imports from countries involved in the Belt and Road Initiative rose by nearly 27 percent, compared with an 18.7-percent increase in overall imports, and its trade with those countries topped 1 trillion dollars, up almost 18 percent year on year.

While protectionism threatens to derail global trade, the Belt and Road Initiative looks set to define the 21st century by cutting global deficits in peace, development and governance. Over a hundred countries and international organizations are now on board.

As Xi said in an article published last month, the initiative offers a pathway to common development through improved infrastructure and connectivity and greater synergy of development strategies.

In just five years of experimentation and exploration, with visions becoming promises and promises turning into projects, the Belt and Road Initiative has emerged as one of the most important globally beneficial projects for international cooperation in modern history.

Projects in Xinjiang only scratch the surface of the opportunities under the initiative, and changes are first felt in Silk Road locations like Kashgar, the Alataw Pass and Horgos.

The most powerful change, however, is probably the changing perspectives.

As the Loeffler's 19-year-old son, Tobias said, "I knew little about the Silk Road, but now I am intrigued. After living in a foreign country like China, I know how much there is to see and do, and how great it can be."