Sonam Tobgye, whose parents were serfs in old Tibet, once lived in an adobe house without windows next to the cowshed.

Two spoons of zanba, a traditional Tibetan staple food made of barley flour, were all that his parents earned for each meal from their lord, while children younger than 13 were given nothing despite a day's hard work.

"Hunger during childhood has become a memory that I can never forget," said Sonam Tobgye, now 78, from the rural area of Comai County, southwest China's Tibet Autonomous Region.

Such a plight came to an end in 1959, when the family was granted farmland, grains and livestock. It was then that the family had decent clothes and shoes.

Sonam Tobgye (L) eats the food in "Qiema," a two-tier rectangular wooden box containing roasted barley and fried wheat grain, in his brother's home in Comai County, Shannan, southwest China's Tibet Autonomous Region, March 15, 2022. (Xinhua/Lodro Gyatso)

In March 1959, the central government led the people in Tibet to launch the democratic reform, abolishing Tibet's feudal serfdom under a theocracy. In 2009, the regional legislature announced March 28 as a day to commemorate the emancipation of about 1 million serfs.

Now, the shabby adobe house of Sonam Tobgye's family has been replaced by a two-story concrete Tibetan building, and the members of his extended family have new jobs: cleaner, driver, teacher, doctor and public servant.

FROM SERFS TO MASTERS

In early 1960s, elections were held across Tibet. For the first time, the former serfs were able to enjoy democratic rights as their own masters.

Sonam Tobgye witnessed an election for the first time in his life. As the emancipated villagers were illiterate, each of them was given a bean for voting.

"Candidates turned their back, leaving their hats on the ground. Villagers then threw their beans into the hat of an ideal candidate as a vote," he recalled.

Following the election, many emancipated serfs took up posts of leadership at various levels in the region.

In old Tibet, serfs accounted for 95 percent of its population. Now, they are masters of the country. The region has more than 35,000 deputies to the people's congresses at various levels and more than 8,000 political advisors.

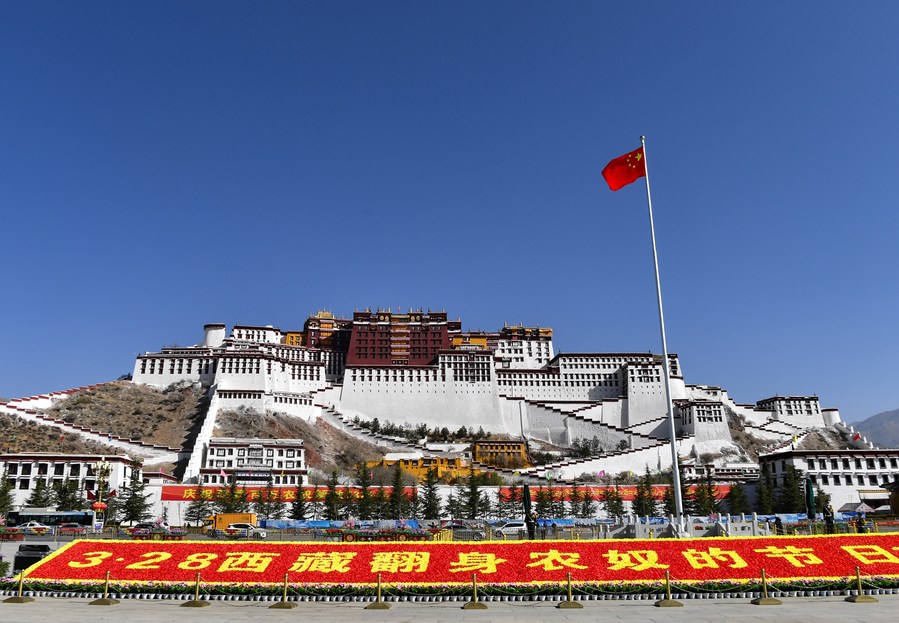

A flag-raising ceremony is held to celebrate the Serfs' Emancipation Day at the square in front of the Potala Palace in Lhasa, capital of southwest China's Tibet Autonomous Region, March 28, 2022. (Xinhua/Jigme Dorje)

"In the old Tibet, women were not allowed to participate in military and political affairs. Now, we have shouldered 'half the sky,'" said Penpa Lhamo, an associate researcher of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and a national political advisor.

At the annual national "two sessions" held in Beijing earlier this month, she submitted a proposal on rural vitalization in border areas.

FROM POVERTY TO PROSPERITY

Farmer Tenzin Wangchug lives at the foot of the Yumbulagang, Tibet's first palace, dating back more than 2,000 years, in Nedong District in the city of Shannan. Prior to the reform, his family had to pay various taxes to the landowner, but Tenzin is free of this burden. His son Basang uses machines to plow barley, wheat and rapeseed on their own farmland spanning 1.3 hectares.

According to the regional agriculture and rural affairs department, the grain output of Tibet reached a new high of 1.07 million tonnes in 2021.

A farmer operates a harvester to reap highland barley at Kere Village of Dagze District in Lhasa, capital of southwest China's Tibet Autonomous Region, Sept. 6, 2021. (Xinhua/Sun Ruibo)

Basang also provides horse-riding services to tourists for the mountainous journey to Yumbulagang, making around 10,000 yuan (1,570 U.S. dollars) a year.

Tenzin Wangchug's two grandsons are public servants, while his grandson-in-law is a taxi driver and runs a garden resort.

By the end of 2019, all registered poor in Tibet had risen from poverty, marking the end of absolute poverty in Tibet, according to a white paper released last year. The region's GDP surged to 208 billion yuan last year from 174 million yuan in 1959.

At home, Tenzin Wangchug likes playing with his three great-grandchildren, two of whom attend a nearby kindergarten.

Students attend a Tibetan class at the Qamdo Experimental Primary School in Qamdo, southwest China's Tibet Autonomous Region, Oct. 5, 2020. (Xinhua/Jigme Dorje)

In old Tibet, there was not a single proper school. With the central government's heavy spending on education over the past seven decades, Tibet now has 3,195 schools of various types and at various levels, hosting more than 790,000 students. Students there enjoy 15 years of publicly funded education.

Last year, Tenzin Wangchug's family spent 170,000 yuan expanding their house, which now has five bedrooms. The living room is bathed in sunshine and full of flowers in bloom.

"Who would ever have thought that life would become this beautiful?" he said.