Talent management expert Li Wenjing, 36, was close to despair in June when she decided to quit her full-time job at a leading multinational company due to the numerous business conferences she had to attend.

"I felt as though I was drowning in an endless wave of meetings that had extremely limited outcomes. I didn't see any meaning in my work. This made me feel bad," she said.

A coach gives swimming lessons in Qingdao, Shandong province. WANG JILIN/FOR CHINA DAILY

For the first time in 12 years, Li quit a job without securing the offer of another. She spent two months traveling in China with her family, which was her longest vacation since she started her career. When the holiday ended, Li decided to embrace flexible employment, and now owns a human resources consulting business, where she has two other full-time employees.

Co-working with two professionals-one in the United Kingdom and the other in Denmark-she offers consulting services on organizational design and development, using the experience gained from all the companies she has worked for. Her income has risen and she works flexible hours.

She spends more time with her 5-year-old son, does not have to commute to and from work each day, and there is no need to attend numerous meetings.

She also works with a number of consultants. Collectively, Li and the consultants are known as gig workers.

When Diane Mulcahy, author of The Gig Economy: The Complete Guide to Getting Better Work, Taking More Time Off, and Financing the Life You Want, was asked to define the idea of the gig economy during an interview in 2017, she said anyone who is a consultant, contractor, freelancer, part-time worker or on-demand worker, is part of this economy.

Basically, there are many ways to describe gig workers, but they all point toward a shift in the way people operate, with more of them deciding their working hours.

In China, while the concept of flexible employment is increasingly favored, particularly by younger people, gig workers are mostly fostered through robust development of the internet and technology.

Bao Chunlei, associate researcher at the Chinese Academy of Labour and Social Security, or CALSS, said flexible employment refers to working hours, locations and payments that are not fixed, different from a conventional employment format based on industrialization.

At a Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security news conference in May, it was disclosed that China had some 200 million workers in flexible employment.

China is advancing its economic transition, and these workers reflect a nationwide trend. The services sector has most flexible employment, and it contributes to 54.5 percent of China's GDP.

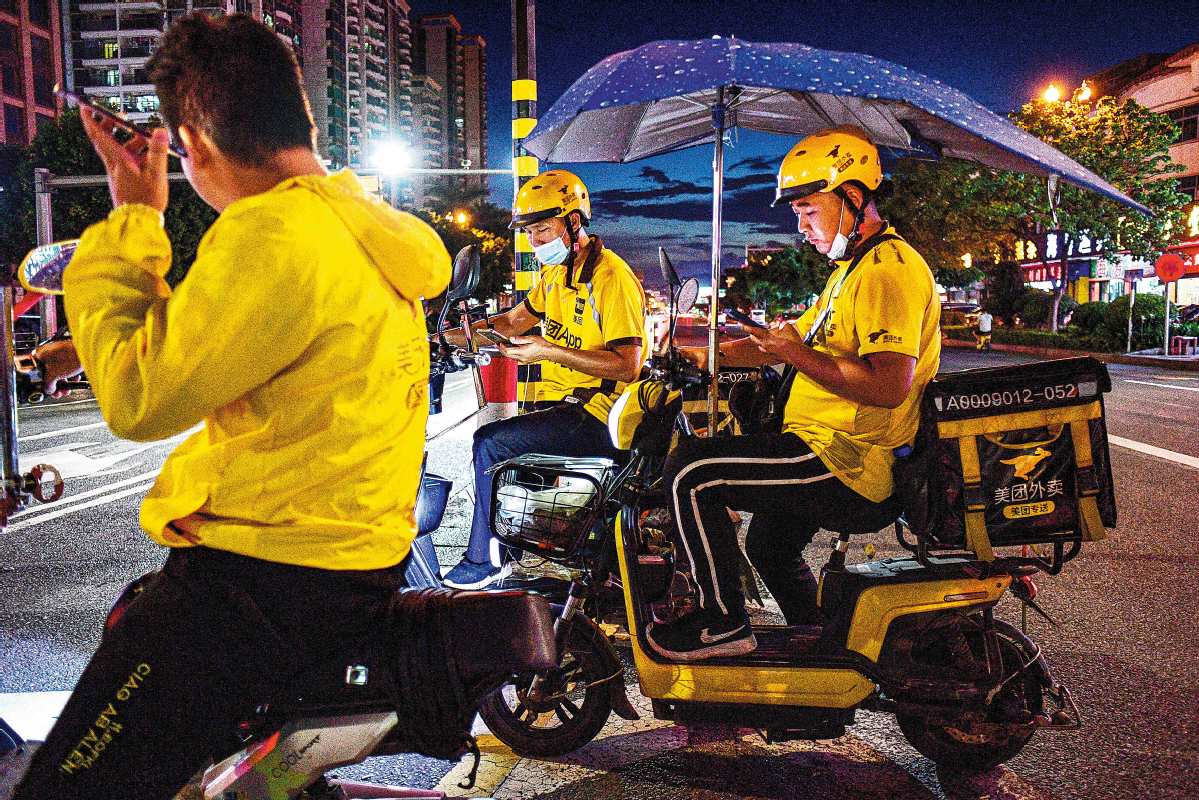

Deliverymen work in Dongguan, Guangdong. ZHAN YOUBIN/FOR CHINA DAILY

Not so lucky

Li said she had little to worry about when she started a project-based career on her own. After 12 years in talent management and organizational development, she had an outstanding resume and was well-connected in her field. Her previous clients continued to approach her with work.

However, many such workers are not so fortunate. Most of them leave full-time positions without knowing what the future holds.

Wu Guoyuan, an independent career consultant who liaises regularly with Li, said that when he became self-employed in 2007, he struggled to break even, as it takes time to build a good reputation among clients.

According to labor economists, although tough starts are commonly experienced by those working flexible hours, the strong growth of technology and the internet has helped greatly in making gig employment an ideal choice.

The fast-growing, internet-based platform economy has produced tens of millions of gig jobs, providing workers with a cushion when they switch careers. Educational qualifications and age requirements for such jobs are far more relaxed compared with other employment, making it easier for migrant employees to find employment in cities.

Zhang Yongqiang, 38, who works for food delivery company Meituan in Beijing, failed twice as a snack bar owner before deciding to become a full-time deliveryman in 2016.

"I was a good chef for 15 years, but I am a terrible business owner. I could have worked as a chef elsewhere, but the salary was not that good," he said.

Initially, Zhang only worked part-time for Meituan, but as his earnings soon exceeded those he made from working eight hours a day as a chef, he had no hesitation in becoming a full-time deliveryman.

To earn more, Zhang takes as many delivery orders from the Meituan platform as possible. When he met other deliverymen at busy food courts, he quickly learned the tricks of the trade from them, such as the most effective delivery routes and the location of toilets on different streets.

For Spring Festival last year, Zhang decided against returning to Shanxi, his home province, for a reunion with his wife and two children, choosing instead to work during the holiday to receive bonus payments from Meituan.

However, COVID-19 forced many restaurants and shops to close during the holiday and in the weeks that followed. People opted to stay home, relying on deliveries for essentials such as food and medicine.

As many deliverymen were unable to return to Beijing due to stringent quarantine requirements, Zhang handled far more orders than usual. With additional payments from the platform and tips from clients, his income rose considerably.

He bought a two-bedroom apartment in Shanxi, and plans to pay off his mortgage by 2024.

Labor economists in China are studying and paying increasing attention to workers such as Zhang. They believe that while solving livelihood problems, flexible employment has also relieved pressure on urban labor.

Bao, from CALSS, said, "A recent report on China's shared economy shows that when the pandemic hit, new business models such as delivery and ride-hailing services showed great resilience and development potential.

"Shared services, new consumption formats and new models have become important ways in China to enhance economic resilience and vitality. With the pandemic raging globally, disrupting people's lives and economies, flexible employment in China has demonstrated unique advantages. It has played a more prominent role in preventing and controlling the pandemic and in the country's efforts to resume work and production."

Throughout last year, when the impact of COVID-19 was most pronounced in China, consumption still accounted for 54.3 percent of the country's total GDP.

Feng Jun, 40, a self-employed wedding photographer in Hefei, Anhui province, said his friends admire him for doing what he loves as a career. However, in the first half of last year he experienced financial problems when nearly all his clients cancelled weddings due to strict social distancing requirements.

He earned little for four months, but still had to pay rent for his studio and also faced other expenses. "I guess such uncertainty and instability come with the territory when you choose a career like this," Feng said.

Zhang, the deliveryman, worries less about fluctuating income, but as he is paying his own social insurance payments in Shanxi, it is difficult for him to get reimbursement when he sees a doctor in Beijing.

Meeting the media last year, Premier Li Keqiang said: "Some 100 million people are now employed in new forms of business and industry, and some 200 million people are working in the gig economy. The government must continue to provide support and at the same time lift all unwarranted restrictions that prevent the development of those industries and sectors."

Photographers work at the China International Aviation& Aerospace Exhibition in Zhuhai, Guangdong, last month. CHINA DAILY

Employment plan

In August, the State Council, China's Cabinet, released a plan to promote employment during the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021-25).

The State Council plan stresses the need to regulate flexible employment growth by getting rid of obstacles and protecting the rights of workers, including couriers, food delivery riders and ride-hailing drivers.

Bao said: "To effectively better protect the rights and interest of gig workers, the definitions 'gig worker' and 'flexible worker' need to be more clearly and specifically defined. A filing system is also needed to get these people registered under a new employment format, and a statistical and investigation mechanism should be set up."

He added that as this form of employment is still new and emerging in China, numerous details are still being studied and refined.

Bao said policies should be drawn up to support flexible employment. In particular, the safety net of Internet Plus public services should be enhanced to enable gig workers to enjoy public services through various channels.

The Internet Plus initiative was created by the central government to transform, modernize and equip traditional industries to join the modern economy.

Bao also called for concrete efforts to strengthen weak links in protecting these workers' basic rights, suggesting that a multi-pronged, coordinated regulatory mechanism be set up involving different stakeholders.

"Internet platforms, which are now major providers of gig jobs, should be included in the coordinated regulatory framework and take a certain degree of regulatory responsibility in protecting the rights and interests of gig workers," he said.

The younger generation in China appears to be embracing the opportunities offered by flexible employment.

When Feng, from Hefei, quit his job to become a photographer in 2012, his parents were worried and would have preferred him to take a position at a large company.

But for 24-year-old astronomy photographer Zhang Jingyi, who lives in Beijing, her parents fully supported her decision to become an independent photographer.

Zhang started work as an astronomy photographer in the Chinese capital immediately after finishing her master's in Australia.

She has never worked regular hours, and may never have the desire to do so. When she was 23, Zhang was a finalist for the Astronomy Photographers of the Year award by the Royal Observatory Greenwich in London. Her photograph of a dragon-like shape in the sky over Iceland was adopted by the NASA website in the United States.

Bao said, "In principle, the robust growth of the gig economy and flexible employment in all forms is significant evidence of China's market-oriented reform and opening up. Young people today are being raised in a society that encourages entrepreneurship, giving them the courage and determination to do what they love, but we still need to build a sound institutional framework for them to grow healthily. As researchers, we have much work to do in this regard."

Two weeks ago, David Card from the University of California, Berkeley, was announced as one of the recipients of this year's Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his empirical contribution to labor economics.

"This will surely bolster our confidence in further research in this regard, particularly in China," Bao said.