Grassland degradation a factor behind sandstorm

We should not blindly pursue the economic benefits of grasslands, but should treat grasslands as ecological products instead and try to achieve their economic value.

By Zhou Muzhi

From March 14 to 15, northern China was hit by the worst sandstorm in a decade. Beijing was shrouded in sick brown dust on March 15, as levels of PM10 surged to 2,153 micrograms per cubic meter. The severe air pollution sparked a heated debate.

Photo taken on Aug. 12, 2020 shows a sand barrier near the Xar Moron River in Hexigten Banner, north China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. (Xinhua/Liu Lei)

The sandstorm swept across 13 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions across China, including Xinjiang, Qinghai, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Ningxia, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Hebei, Beijing, Tianjin, Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang, affecting more than 120 million people.

What caused such a massive sandstorm? The meteorological authorities concluded it was the rising temperatures, decreased rainfall, and gusty winds in Mongolia and northwestern China that provided thermal and dynamic conditions for the formation of the sandstorm. In fact, another major environmental factor causing the sandstorm is grassland degradation, and even desertification.

The massive sandstorm was considered to start from Mongolia. Many experts blamed farming and overgrazing for the accelerated desertification of Mongolia's grasslands. Grasslands perform functions of preventing winds, fixing sand, purifying air, absorbing CO2, adjusting climate and conserving water source, and play an important role in improving human living environment. Improper exploitation has wreaked havoc on grasslands. There is a global consensus on the recognition of the importance of grasslands and crises.

Distribution, and increase and decrease of grasslands

What is the status quo of China's grasslands? According to the satellite remote sensing data of grassland areas, provided by Cloud River Urban Research Institute's latest "China Integrated City Index 2019," China's grassland resources feature an uneven distribution.

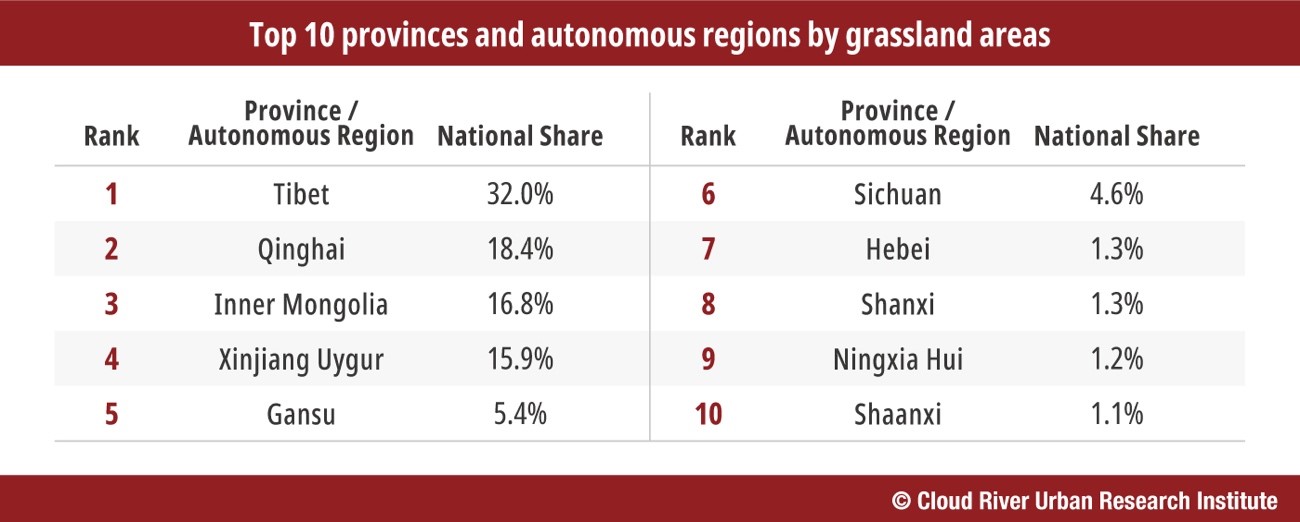

Specifically, Tibet, Qinghai, Inner Mongolia, and Xinjiang take the top four spots in the ranking in terms of grassland areas, accounting for 32%, 18.4%, 16.8% and 15.9% (83.1% combined) of China's total grassland resources, respectively. The top 10 provinces and autonomous regions in the ranking make up 97.9% of the country's total.

Grasslands are one of China's largest land resources, and serve as an important hub of material circulation and energy flow in the ecosystem, but they are concentrated in southwestern, northwestern and northern China.

Chart: Top 10 provinces and autonomous regions by grassland areas

Among the 297 Chinese cities at prefecture level and above, Naqu, Shigatse, Chamdo, Hulunbuir, Ordos, Chifeng, Shannan, Jiuquan, Nyingchi, and Ulanqad, which are the top 10 in the league table, account for a combined 31.3% of the country's total grassland area. However, their permanent resident population only makes up a combined 1.1% of the country's total, their GDP only 0.9%, and their GDP of the first industry only 1.7%. That means the top 10 cities have the most grassland resources, but occupy a small proportion of the country's total population, GDP and the first industry.

Chart: Top 30 cities by grassland areas

Looking at the top 30 cities by grassland area in the ranking, we observe the same situation. The top 30 cities in the ranking boast 41.5% of China's grassland. However, their permanent resident population, GDP, and GDP of their first industry make up 4.4%, 3.8%, and 5.5% of the country's total, respectively. The per capita GDP of the top 30 cities, though vast and underpopulated, is only 83.5% of the country's average level.

Those figures provide a perspective at the national level that grasslands play an extremely important role in the ecological environment, but their carrying capacity of population and GDP contribution are not big. Moreover, grassland ecology is quite vulnerable.

In many regions, farming, overgrazing, mining, herbal picking and other improper exploitation ways are eroding the valuable and vulnerable grassland resources.

From 2017 to 2018 alone, China's grassland area shrank by 8,185 square kilometers. The figure was shocking, as it accounted for merely 0.26% of the country's grassland area, but was larger than the urban area of Guiyang city. China's efforts in protecting the ecological environment have paid off in recent years, as 70 cities in 297 cities saw their grassland areas increase. It is worth noting that grassland areas in 227 cities are getting smaller, and the effort taken by those cities in protecting grasslands is far below efficiency.

Ecological products and functional zones

The sandstorm taking place on March 15 warned that over exploitation of grasslands not only brings environmental devastation, but also a disaster to our living environment.

I agree with the idea of "ecological products" proposed by Yang Weimin, a member of the Standing Committee of the CPPCC National Committee. We should not blindly pursue the economic benefits of grasslands, but should treat grasslands as ecological products instead and try to achieve their economic value. Of course, to realize the value of grasslands as ecological products, we need to purchase ecological products through the central government's finance, exchange ecological value between regions, sell water rights, emission rights, and carbon emission rights, realize the price premium of ecological products, and charge for tourism products. All these ways need the protection of policies and systems.

The system of functional zones, which has been implemented in China, serves as the framework mechanism for building this kind of policy system. The main functional zones divide the land space into four types: optimized development areas, key development areas, restricted development areas and prohibited development areas. Different development policies are implemented for different areas. Policies of "converting farmland to forests" and "converting farmland to grassland" in restricted development areas and prohibited development areas, as well as policies of restricted and prohibited development, aim to reduce production space and increase ecological space.

China's grassland resources mostly concentrate in limited development areas and forbidden development areas. With improving and implementing the system of functional zones, grassland resources can be restored in the long run. Whether it is the construction of systems and mechanisms, or the implementation, we still have a long way to go before we truly turn lucid waters and green mountains into invaluable assets.

The author is head of Cloud River Urban Research Institute.