Global COVID-19 responses: 'Zero COVID-19 Case Policy' vs. 'Coexisting with COVID-19 Policy'

How come the metropolises around the world with concentrated medical resources are so vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic? Why China has managed to control the outbreak so quickly? Why Western countries and Japan are seeing a resurgence in the coronavirus outbreak? Professor Zhou Muzhi, president of Cloud River Urban Research Institute, offers his interpretation by comparing the COVID-19 responses adopted by different countries around the world.

By Zhou Muzhi

2. A test for the health care system

Wuhan was the first to confront the COVID-19 outbreak. The city climbed one place to the sixth in the 2019 health care radiation ranking, as it boasts 27 3A-grade hospitals, nearly 40,000 physicians, 54,000 nurses and 95,000 beds. It is hard to expect that a city with such strong health care capacity could be overwhelmed by the coronavirus epidemic.

Other metropolises like New York and Milan are equally vulnerable to the pandemic. Tokyo, which declared?a?state?of?emergency on April 7, was also facing a breakdown of its medical system. The novel coronavirus is indeed a test for the health care system in all global cities.

In the April article, I believe that three reasons are attributed to the breakdown of the cities' medical system.

(1) Overloaded hospitals

One feature of the COVID-19 epidemic is the exponential growth of infections. Especially during the early stage of the outbreak, the surge in infections and social panic have driven a lot of people, whether they were infected or not, to seek testing and treatment in hospitals. This has caused disorder, leaving those who are critically ill unable to receive efficient and quality care. It is also a reason for its high fatality rate. Moreover, the overcrowded emergency rooms, with confirmed cases, suspected patients as well as their families, can also lead to many hospital-acquired infections (HAIs).

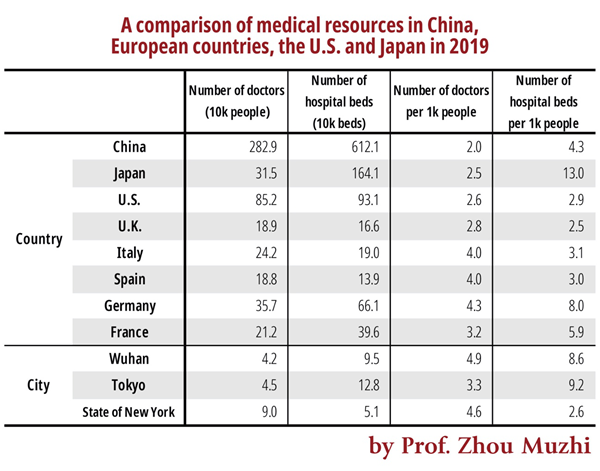

As is seen from Table 1, the density of physicians in the U.S., Japan and China are only 2.6, 2.5 and 2 per 1,000 people respectively, much lower than that in Germany (4.3), Italy (4) and Spain (4).

Wuhan, with a large concentration of medical resources, has 4.9 physicians per 1,000 people, which is much higher than the national average. But the city's medical system was still overstretched by the outbreak. By May 11, the day before the April article's Japanese version was published, 83.3% of the COVID-19 deaths in China had happened in Wuhan[5], which is believed to be caused by the overloaded hospitals.

Just like in Wuhan, medical workers in the U.S. are also concentrated in big cities. The New York state has 4.6 physicians per 1,000 people, but it is still not enough to avoid a massive breakdown in its medical system.

Italy, one of the hardest-hit countries in the pandemic, has a relatively high density of physicians, counting 4 per 1,000 people, but the country still suffers seriously overloaded hospitals and a breakdown in its health care system. In the Lombardy region where Milan is located, the number of infections has quickly risen from 1,000 on March 2, to over 10,000 on March 14, and to over 40,000 by the end of March. Many patients with critical conditions could not be treated in time due to overcrowded emergency rooms. By May 11, a total of 220,000 people in Italy had tested positive for COVID-19, and the death toll was 31,000, driving the fatality rate to 14%.

Japan's Tokyo has 3.3 physicians per 1,000 people, lower than the level in Wuhan and the New York State. Therefore, the Japanese government has been trying to avoid overcrowded emergency rooms as a key part of its COVID-19 response. The government has established a pre-testing approval procedure to limit the number of testing and advised residents not to go to hospital during the pandemic to reduce hospitalization [6]. Japan's measures are so far effective to reduce the number of HAIs and lower the fatality rate as the medical resources are mostly given to those with critical conditions. By May 11, Tokyo's fatality rate was 5.3%, compared to 7.9% in New York State.

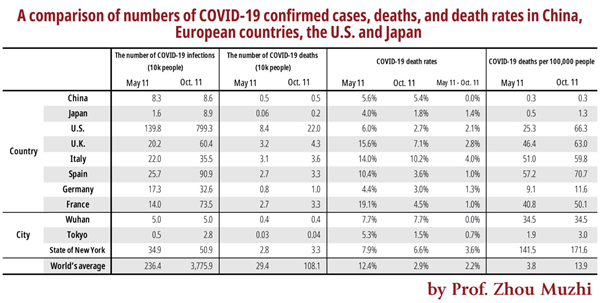

Table 2 compares statistics between May 11 and Oct. 11, showing the COVID-19 infections, death toll, fatality rate and the number of deaths per 100,000 people in China, Japan, the U.S. and major European countries, as well as cities like Wuhan, Tokyo and New York.

By May 11, Spain had 56.9 deaths per 100,000 infections, Italy had 50.5, France 40.4, the U.S. 24.4, and Japan only 0.5. In this sense, Japan successfully controlled the number of deaths in the first outbreak after it avoided a breakdown in its medical system.

From the statistics by May 11, France's COVID-19 fatality rate was up to 19.1%, and the U.K., Italy, and Spain also recorded double-digit fatality rate, while the rate in China and Japan were only 5.6% and 4%. At the same time, the global average COVID-19 fatality rate was up to 12.4%, which dealt a heavy blow to the human society.

However, from May 11 to Oct. 11, those countries and cities had seen a significant drop in COVID-19 fatality rate. During that period, China had zero COVID-19 death cases, while Japan controlled the rate at 1.4%. France and Spain which previously had very high fatality rate managed to lower it under 1%. Even the U.S. which had over 200,000 COVID-19 deaths also lowered the rate under 2.1%.

The reduction was attributable to less crowded emergency rooms compared to the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak. Though there is no specific medicine that can cure the disease, each country has, to some extent, found ways to treat their patients, which is also key to lowering the rate. Moreover, mass testing is another important reason.

In a period of five months, the global fatality rate lowered to 2.2%. It seems that the new virus is becoming less intimidating. Actually, the rate varies widely between different age groups. Chances of a relatively younger person dying from coronavirus is much lower than that of a relatively older person. For example, Japan's fatality rate in August was 0.9%. By different age groups, the rate for people who are 69 or younger is only 0.2%, but the figure ghastly spiked to 8.1% for those who are 70 or older.

In his address to the Economic Club of New York on Oct. 14, the U.S. President Donald Trump said that 99.98% of the infected under the age of 50 can survive, but the seniors who had underlying conditions have higher risks. Therefore, protecting the high-risk groups through improving the prevention and control system is key to lowering the fatality rate.