III. The trade protectionist practices of the US administration

The numerous investment and trade restriction policies and actions adopted by the US that distort market competition, hamper fair trade, and lead to breakdowns in global industrial chains are detrimental to the rules-based multilateral trading system and severely affect the normal development of China-US economic and trade relations.

1. Discrimination against foreign products

Many American regulatory policies are clearly self-serving and protectionist as they run counter to the principle of fair competition and discriminate against foreign products. The US directly or indirectly restricts the purchase of products from other countries through legislation, subjecting foreign companies to unfair treatment in the US, with Chinese companies being the main victims.

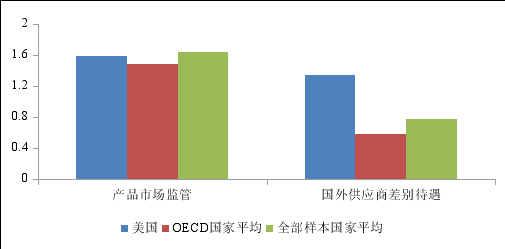

The US product market falls behind most developed countries and even some developing countries in terms of fair competition. According to the statistics on Indicators of Product Market Regulation1 released by the OECD in 2013, the Netherlands, the UK and Australia were the top three among 35 OECD countries, while the US ranked only 27th, pointing to the many obstacles created by the US market regulatory policies for fair competition in the product market. When the indicators of 12 non-OECD countries were added, the US ranked only 30th among the 47 countries, indicating a product market environment less fair than those of non-OECD countries such as Lithuania, Bulgaria and Malta.

The US is far more discriminatory against foreign products than most developed countries and even some developing countries. According to the ranking of 35 OECD countries on Differential Treatment of Foreign Suppliers2, a secondary indicator of the Indicators of Product Market Regulation, the US ranked 32nd among 35 OECD countries in 2013, indicating severe discrimination against foreign countries in its product market. When the indicators of 12 non-OECD countries were added, the US ranked 39th among the 47 countries, with a higher degree of discrimination than such non-OECD countries as Brazil, Bulgaria, Cyprus, India, Indonesia and Romania (Chart 7).3

Chart 7: The Extent to Which US Market Regulatory Policies Inhibit Fair Competition in the Product Market

Source: OECD, Indicators of Product Market Regulation, 2013

The US, by way of legislation, sets strict requirements on its government departments to "buy American" and imposes discriminatory terms on purchasing foreign products. For example, the Buy American Act stipulates that US federal agencies can only acquire manufactured products made in America and unmanufactured articles that have been mined or produced in America.4 According to the Code of Laws of the United States of America, an application for a public transport project receiving federal or state funding can be granted only if the steel, iron and manufactured goods used in the project are produced in the US.5 According to the Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, none of the funds made available by this Act may be used to procure raw or processed poultry products imported into the US from China for use in the school lunch program, the Child and Adult Care Food Program, the Summer Food Service Program for Children or the school breakfast program.6 The National Defense Authorization Act prohibits the federal government from procuring telecommunications equipment and services provided by Chinese companies on the grounds of national security.7

2. Abuse of "National Security Review" as a way to obstruct the normal investment activities of Chinese companies in the US

The US is the first in the world to conduct security reviews on foreign investment. In 1975, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) was established for the specific purpose of monitoring the impact of foreign investment in the US. In 1988, the Exon-Florio Amendment revised the 1950 Defense Production Act by mandating the US President and people with the authority to review foreign takeovers. The Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 expanded CFIUS and broadened its scope of review.8 The legislation process in the US over the past 50 years shows that the US security review of foreign investment has mainly been characterized by tighter laws, regulations and policies, expanded regulatory teams and scope of reviews, and more recently, intensified screening and restrictions vis-à-vis China.

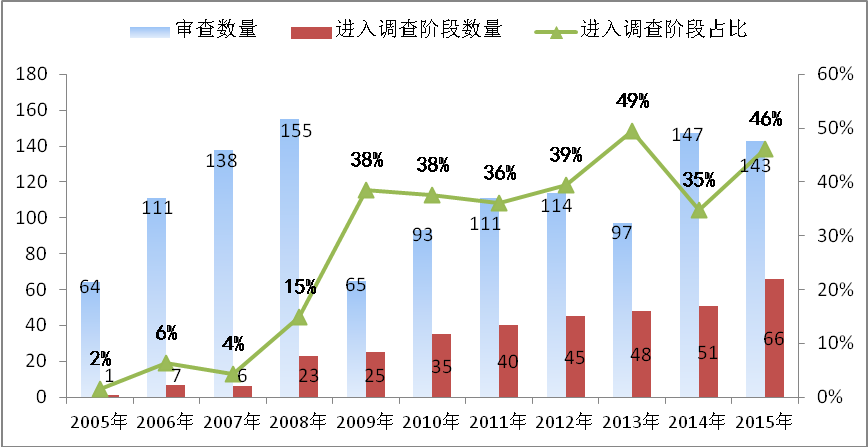

In practice, the US "national security review" is often based on flimsy evidence and is becoming increasingly stringent. According to CFIUS annual reports to Congress,9 the Committee reviewed 468 foreign investment transactions from 2005 to 2008, only 37 of which (8 percent) entered the stage of investigation. However, since the Department of the Treasury issued the Regulations Pertaining to Mergers, Acquisitions, and Takeovers by Foreign Persons10 in 2008, among the 770 cases reviewed between 2009 and 2015, 310 cases – 40 percent of the total – passed on to the stage of investigation, which represents a noticeably sharp rise. In particular, the latest data released in 2015 shows this percentage climbing to an even higher level of 46 percent (Chart 8).

Chart 8 Statistics on Cases Reviewed and Investigated by CFIUS

Source: Annual Reports Released by CFIUS

Chinese companies are one of the main targets of the US abuse of national security reviews. Since the establishment of CFIUS, US Presidents vetoed four transactions based on the Committee's recommendation, all targeting Chinese firms or their related businesses. From 2013 to 2015, CFIUS reviewed in total 387 transactions concerning 39 economies, among which 74 were transactions involving investment from Chinese companies, accounting for 19 percent of the total, the largest share among all countries for three years in a row. The data on Chinese corporate investment being vetoed and blocked by the US (Table 4 and Table 5) shows that CFIUS review of Chinese investment has extended its reach from semiconductors and financial sectors to food processing sectors including swine feed. In addition to an absence of transparency in the review process, excessive discretionary power, and lack of explanations for vetoes, there is an even more serious issue – that normal transactions are being obstructed on the grounds of national security.

Table 4: Overseas Acquisition Transactions with Chinese Investment Vetoed by the US from 1990 to 2018

Year | Buyer | Target | Sector |

1990 | China National Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation (CATIC) | MAMCO (Manufacturer of Aircraft Parts) | Manufacturing |

2012 | Ralls, Affiliate of Sany Group | Wind Farm in Oregon | Energy |

2016 | Fujian Grand Chip | Aixtron (American Subsidiary of a German Chip Maker) | Semiconductor |

2017 | Canyon Bridge | Lattice Semiconductor Corporation from Oregon | Semiconductor |

Table 5: Chinese Companies' Overseas Acquisitions Revoked as a Result of CFIUS Reviews from 2005 to 2018

Year | Buyer | Target | Sector |

2005 | CNOOC | Unocal | Energy |

2008 | Huawei/Bain | 3Com | Communications |

2009 | Northwest Non-Ferrous International Investment Company Ltd | Firstgold Corp. | Energy |

2010 | Tangshan Caofeidian Investment Corporation | Emcore | Communications |

2010 | Anshan Iron and Steel Group | Steel Development Company | Manufacturing |

2010 | Huawei | 3Leaf | Communications |

2016 | GSR Ventures | Royal Philips' Lumileds (US operations included) | Manufacturing |

2017 | TCL | MIFI of Novatel Wireless | Communications |

2017 | NavInfo, Tencent and GIC | Dutch mapping data provider HERE (US operations included) | Mapping |

2017 | HNA Group | Global Eagle Entertainment | Entertainment |

2017 | Zhongwang International Group | Aleris | Manufacturing |

2018 | Ant Financial | MoneyGram | Finance |

2018 | Da BeiNong Group | Waldo Genetics | Agriculture |

2018 | BlueFocus Group | Cogint | Internet |

2018 | China Heavy Duty Truck Group | UQM | Manufacturing |

2018 | HNA Group | Skybridge Capital | Finance |

Source: Public Information

The United States is preparing new legislation for more stringent foreign investment security review. On August 13, 2018, the President signed the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, part of which is the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA), which strengthens the authority of CFIUS, expands the scope of transactions covered, recruits additional staff, establishes the term of "countries of special concern", and adds additional factors to be considered in reviews. All of this points to a clear trend of tighter investment reviews. In particular, it requests the Department of Commerce to submit a biennial analysis on Chinese investments in the US before 2026.11

3. Large subsidies that distort market competition

US governments at federal and sub-national levels provide large subsidies, bailout assistance, and concessional loans to some sectors and companies. Such actions obstruct, to a large extent, fair market competition. According to Good Jobs First, an American organization that tracks subsidies, between 2000 and 2015, the federal government provided at least US$68 billion in grants and special tax credits to businesses, with 582 large companies receiving 67 percent of the total.12 During the same period, federal agencies gave the private sector hundreds of billions of dollars in loans, loan guarantees, and bailout assistance. A wide range of sectors received government subsidies. Motor vehicles, aerospace and military contracting, electrical and electronic equipment, oil and gas, financial services, chemicals, metals, and retailing and information technologies ranked among the top of the 49 tracked sectors.13 State and local governments also gave enormous subsidies to companies. The amounts of subsidies at the state level are basically not subject to federal jurisdiction, hence the difficulty in assessing their specific scale and nature. Actual amounts of the state-level subsidies are much higher than the disclosed figures.

In the aviation sector, Boeing has received US$14.5 billion of allocated subsidies from the federal and state/local governments since 2000 and US$73.7 billion of loans, bond financing, venture capital, loan guarantees and bailout assistance from governments at various levels since 201114 (Box 5).

Box 5 EU Challenge to US Civil Aircraft Subsidy In 2004 and 2005, the EU twice requested consultations with the United States concerning subsidies provided to Boeing. In 2006, the WTO established the DS353 panel. In March 2012, the WTO Appellate Body report affirmed the value of prohibited and/or actionable subsidies granted by NASA, the Department of Defense, the Department of Commerce and other federal departments, and the States of Washington, Kansas and Illinois to Boeing over a long period, in the form of research and development assistance by the federal government and tax credits by governments at other levels, to be at least US$5.3 billion, and called upon the United States to revise its subsidy policy in compliance with WTO agreements. The United States expressed its intention to implement the rulings over a six-month period. In November 2013, the State of Washington revised its local tax legislation and announced an extension of the tax credit policy for domestic aviation companies to keep Boeing assembly lines in the State. The EU made several accusations about the US non-compliance. On June 9, 2017, the WTO issued a report which ruled that the State of Washington was still providing prohibited subsidies to Boeing. The report confirmed significant lost sales of the A320neo and A320ceo families in the large civil aircraft market and a threat of impedance of exports of A320ceo to markets in the United States and the United Arab Emirates due to the State of Washington's tax reduction policy for Boeing. The policy violated the US commitment to compliance with the rulings in 2012. |

In the automotive industry, the US government at both federal and state levels supports the auto industry with preferential policies and provides key auto companies with large bailouts and disguised subsidies. During the global financial crisis, the US government, with its Automotive Industry Financing Program (AIFP) under the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TAPR), provided key auto companies with nearly US$80 billion of assistance.15 In 2007, the US Department of Energy, citing Section 136 of the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, introduced the Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loan Program (ATVM), with authorization from the US Congress, to provide up to US$25 billion in loans.16 Since 2000, Tesla has received more than US$3.5 billion in subsidies from US federal and state/local governments.17

In the field of computer and semiconductor manufacturing, the US has long adopted government-led industrial policies. The US government allocated US$1 billion in the 1980s to SEMATECH to support cutting-edge research, with a view to maintaining America's leading position in this area and preventing over-reliance on foreign suppliers. Apple's research and development on nearly all of its products, including the mouse, the display, the operating system, and the touch screen, received support from US government departments, with some of them created directly in labs run by the government. In the military-defense industry, the US has supported related enterprises with preferential taxes, loan guarantees, procurement commitments, etc. Large military-defense enterprises on the brink of bankruptcy have been offered special government loans, restructuring funds, bankruptcy protection, transitional funds, debt relief and other preferential policies. As provided in the 2014 Defense Production Act, "The President may authorize a guaranteeing agency to provide guarantees of loans by private institutions for the purpose of financing any contractor, subcontractor, provider of critical infrastructure, or other person in support of production capabilities or supplies that are deemed by the guaranteeing agency to be necessary to create, maintain, expedite, expand, protect, or restore production and deliveries or services essential to the national defense". In 2016, Lockheed Martin, the world's largest military-defense company, obtained US$200 million from the State of Connecticut. In agriculture, high subsidies have long been a policy of the US, the birthplace of the majority of agriculture subsidies in the world. As a result of the WTO Uruguay Round negotiations, the US can give all individual items up to US$ 19.1 billion in amber box subsidies. With abundant financial resources and extensive room for subsidies, the US provides high subsidies for its huge agricultural exports. These subsidies undermine fair international competition and have been repeatedly challenged by other countries, a case in point being the 12-year-long dispute with Brazil over the upland cotton subsidy. In 2014, as part of a major adjustment to its agriculture subsidy policy, the US replaced direct subsidy programs, such as the Counter-cyclical Payment, with the Price Loss Coverage Program and the Agricultural Risk Coverage Program. Simply another form of amber box subsidy, these price-pegged subsidies resulted in a higher level of support. Joseph Glauber, the former chief economist of the US Department of Agriculture, pointed out that these two coverage programs, with reference prices set higher than the target prices of the past, in fact raised the level of subsidy support.18 According to the Congressional Research Service, the two programs together cost US$10.1 billion in 2015 and US$10.9 billion in 2016. The 2016-2017 support level was higher than before the introduction of the act in 2014.19 A total of nearly US$15 billion was spent in support of individual items, the highest in nearly a decade.20 The US also boosted its agricultural exports through various forms of credit guarantee programs. On top of that, the US sent a large volume of the excess farm produce abroad as non-emergency food aid, which led to serious problems of commercial substitution, distorting local agricultural markets in the recipient countries, and undermining the interests of other agricultural exporting countries.

4. Use of large-scale non-tariff barriers

While the WTO does not completely prohibit countries from protecting their domestic industries, certain principles must be followed, including lower non-tariff barriers, greater transparency of policies and measures, and a minimal level of trade distortion. The US has put in place a large number of discriminatory non-tariff barriers that are more targeted yet disguised, in an effort to keep specific segments of the domestic market under strict protection. This approach constitutes a notable distortion of the trade order and market environment.

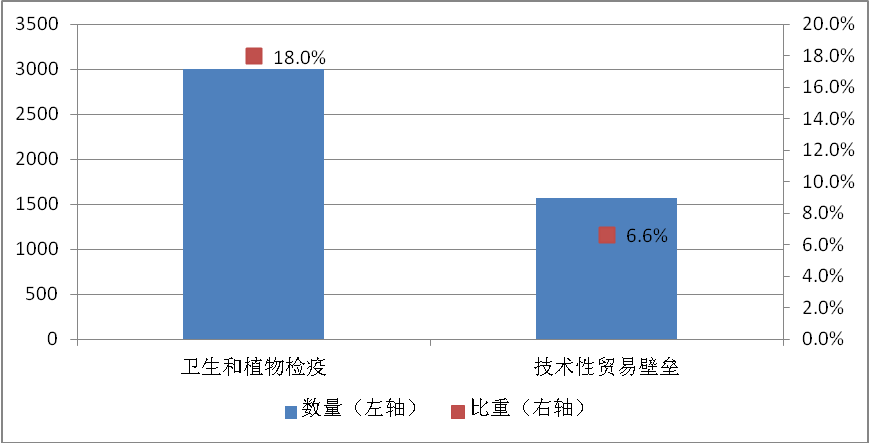

Chart 9: US Non-Tariff Trade Barriers and Its Global Share

Source: WTO Database

According to the WTO, the US has reported 3,004 sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures and 1,574 technical barriers to trade (TBT) measures, accounting for 18 percent and 6.6 percent of the world's total (Chart 9). As reported in the UNCTAD's "Analysis of Trade Regulations Data Flags Important New Findings" on June 29, 2018,21 a tree has to meet 54 SPS requirements before it can be imported into the US. These technical barriers have significantly lowered customs clearance efficiency and raised trade costs.

5. The abuse of trade remedy measures

While the WTO allows the use of trade remedy measures when a member economy finds damage caused to its domestic industries by dumping, subsidy or excessive growth in imports, strict limits and conditions do apply. However, the US has resorted to a huge number of trade remedy measures to protect its domestic industries. Many of these measures target China.

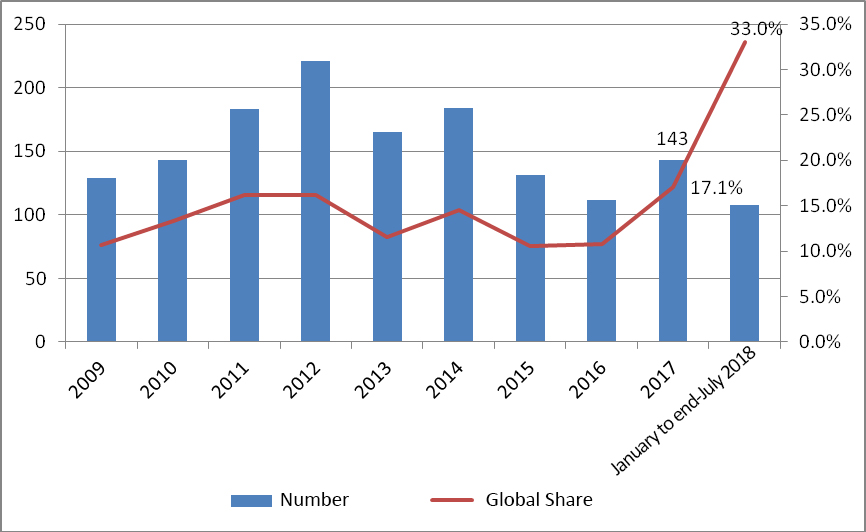

The US is adopting a growing number of trade protectionist measures, whose share of the world's total is also rising. According to Global Trade Alert, among the 837 new protectionist measures adopted in 2017 worldwide, 143 (or 17.1 percent) were from the US. From January to the end of July in 2018, the US accounted for 33 percent of all protectionist measures in the world (Chart 10).

Chart 10: Additional Trade Protectionist Measures of the US and Their Global Share

Source: Global Trade Alert

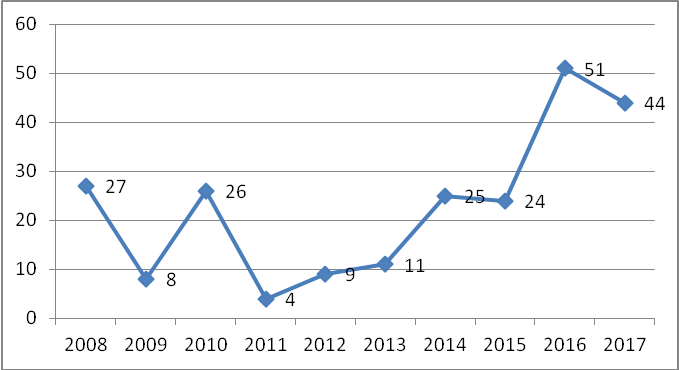

According to the United States International Trade Commission, by July 17, 2018 there were 44 anti-dumping and countervailing measures in effect in the US (Chart 11), among which 58 percent were adopted after the 2008 financial crisis, with China, the EU and Japan as the main targets.

Chart 11: Number of US Anti-dumping and Countervailing Measures Since 2008

Source: United States International Trade Commission

In anti-dumping investigations, the US has refused to honor its obligation under Article 15 of China's WTO Accession Protocol and continued to use the surrogate-country approach, citing its domestic law. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) of the US Congress calculated that the rates of anti-dumping duties applied to countries recognized as market economies are notably lower than those applied to non-market economies (NMEs). The average anti-dumping duty imposed by the US on China is 98 percent, while that on market economies is 37 percent.22 Among the 18 US rulings concerning Chinese products since the start of 2018, 14 had rates of more than 100 percent. Moreover, the US picks surrogate countries rather randomly,23 making the results of anti-dumping investigations highly unfair and discriminatory for Chinese exporters.

1 Indicators of Product Market Regulation measure the extent to which policy settings promote or inhibit competition in the product market. A higher score indicates greater hindrance. The indicators are computed based on three indicators – state control, barriers to entrepreneurship and barriers to trade and investment. Since 1998, the indicators have been computed every five years – in 1998, 2003, 2008 and 2013. Data were collected through surveys filled in by officials from relevant countries. The statistics cover 35 OECD countries and 12 non-OECD countries. Products covered by the statistics also include some services.

2 Differential Treatment of Foreign Suppliers is a secondary indicator for barriers to trade and investment in the indicators of product market regulation. It is computed based on the evaluation of restrictions on shipping, land transport and air transport, on foreign professionals, on appeals by foreign entities, on anti-competition behavior, regulatory policy barriers and trade facilitation measures. It reflects the extent to which a country's market discriminates against foreign products. A higher score indicates greater discrimination.

3 OECD (http://www.oecd.org).

4 The White House (http://uscode.house.gov), Buy American Act. The act has also made additional stipulations for waivers.

5 The White House (http://uscode.house.gov), Buy American Act. The act has also made additional stipulations for waivers.

6 The US Congress (https://www.congress.gov), Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act.

7 The US Congress (https://www.congress.gov), National Defense Authorization Act.

8 The US Congress (https://www.congress.gov), Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007.

9 Based on CFIUS'annual reports to Congress (https://www.treasury.gov)

10 The US Department of the Treasury, November 21, 2008.

11 The US Congress (https://www.congress.gov).

12 Good jobs first (https://www.goodjobsfirst.org), March 2015.

13 Good jobs first (https://subsidytracker.goodjobsfirst.org).

14 Good jobs first (https://subsidytracker.goodjobsfirst.org).

15 The US Department of the Treasury(https://www.treasury.gov).

16 The US Department of Energy (https://www.energy.gov).

17 Good jobs first (https://subsidytracker.goodjobsfirst.org).

18 Joseph W. Glauber and Patrick Westhoff: "The 2014 Farm Bill and the WTO",American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 2015.

19 Randy Schnepf: "Farm Bill Provisions and WTO Compliance", Congressional Research Service, April 22, 2015.

20 Randy Schnepf: "Farm Safety-Net Payments Under the 2014 Farm Bill", Congressional Research Service, August 11, 2017.

21 The UNCTAD (http://unctad.org ).

22 "US-China Trade – Eliminating Non-Market Economy Methodology Would Lower Anti-dumping Duties for Some Companies", a report by the GAO in 2016.

23 Gary Horlick, deputy assistant secretary of the International Trade Administration of US from 1981-1983, talked about the selection of surrogate countries in a Ways and Means Committee hearing. Horlick described the selection as based on perception. For instance, in a towel case with China, the US listed Pakistan, Thailand, Malaysia, the German Democratic Republic, Colombia and India as surrogate countries, for no apparent reason.